The Hereness of Now

There was a day last July when I felt a massive shift. The earth moved beneath me—we had suddenly jumped timelines. I had a deep body feeling that I imagine was similar to what my ancestors felt at various times in history: time to get the fuck out.

It shook me; I was in a period where I was already destabilized in my personal life and nothing in my future was certain or predictable. Not fully belonging anywhere is an experience that has accompanied me since I was a small child. And yet, I knew leaving wasn’t something I’d be doing.

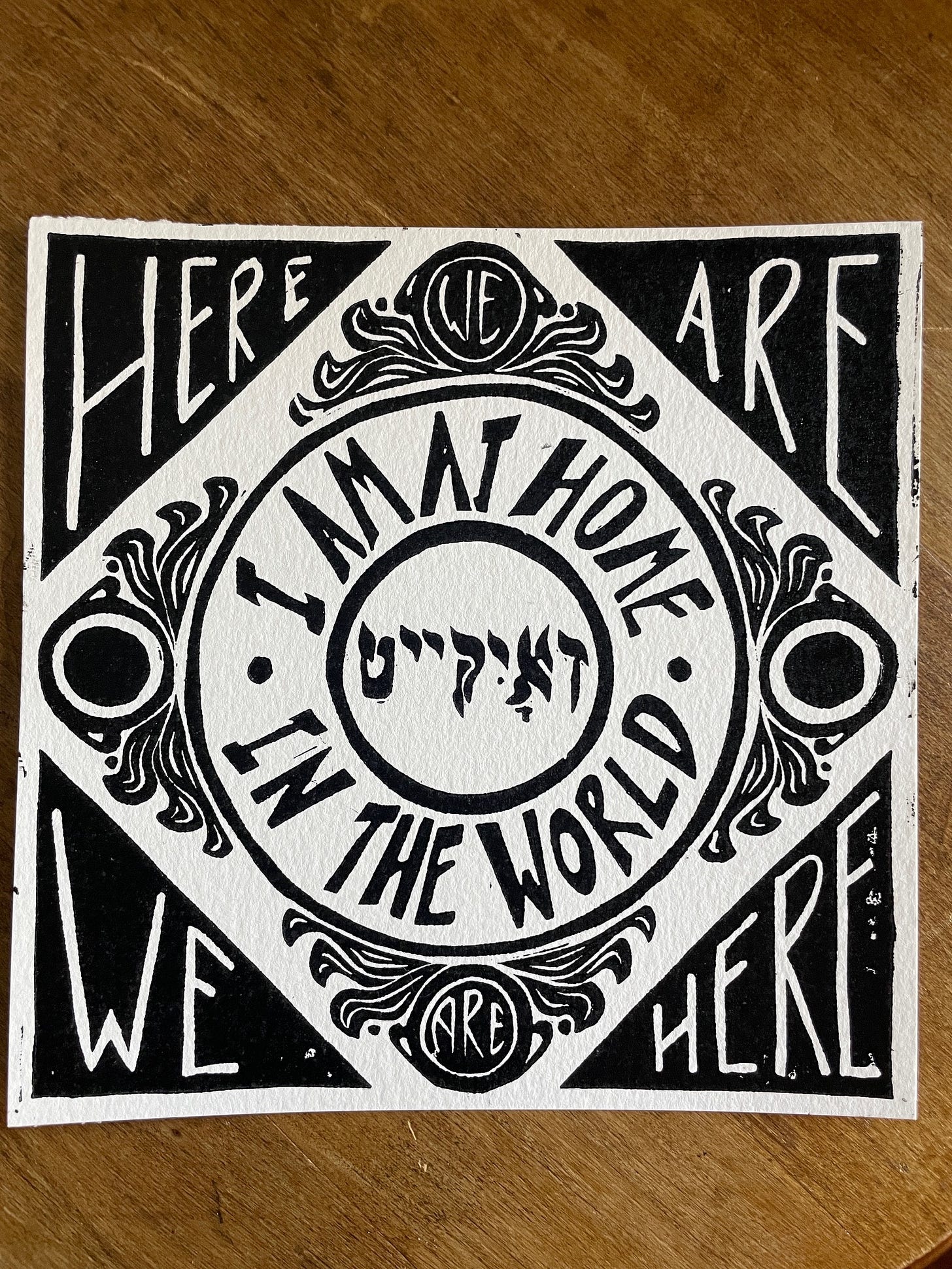

Doikayt is a Yiddish word meaning “hereness.” It grew out of the slogan of the Jewish Labor Bund: “here where we live, that is our country” —a rejection of the combined efforts of antisemitic European leaders and Zionists (whose movement was founded the same year as the Bund) to remove Jews from their home countries. The term has gained considerable traction in recent months, as American Jews have turned to our histories in search of spiritual ancestors who fought against fascism and ethno-nationalism.

Members of the Bund wrote with prophetic clarity about the inevitable results of colonization. They understood the naïveté of thinking that freedom for some lies in the oppression of others: “The answer to tragically but pointlessly spilled blood cannot lie in more national hatred, which will inevitably lead to more communal clashes, but in international solidarity and the growth of the socialist movement.” Similar to later groups such as the Black Panthers in America, they provided youth programs and education, distributed newspapers, and created community defense groups in addition to their labor and rights organizing.

To embrace diaspora, one must hold complicated and sometimes conflicting concepts: the longing for traditions and knowledge—threads severed at slave ports and Ellis Island, drowned by swift currents in borderland rivers, lost in sands of unforgiving deserts; and a pride in the fierce survival instincts of our ancestors and communities. We mourn that assimilation further stripped memories, language, and stories from our histories; we honor the desire for safety that assimilation represented to our forebears. We search for missing pieces; we mend together what we have with stitches of our own. We build new traditions from the old to rise to the occasion of our time.

Living in diaspora is to be everywhere and nowhere—but mostly, it is to reckon with the reality of being right here, wherever that is at this moment. The fight to remain in place is one fought worldwide: against evictions, against pogromist violence, against ICE, against occupying armies, against camp-sweeping cops, against foreclosing banks, against eminent domain, against demolition. America is a country of refugees, of thousands of diasporas overlapping and swirling together. It may be one of the most unifying experiences that we all share: loss of a sense of place.

Creating belonging is a sacred task. There are a million ways to do it, from listening wholeheartedly to someone, to protecting our neighbors from secret police kidnappings. I bet there is something you are already doing that helps people feel that they belong to this world, to this place, or to themselves. Identify these sparks and blow them into a roaring flame.

That day in July, I took a walk by the river. On a bench looking out over the water, there was an inscription: Be here now (the famed Ram Dass quote). We belong to now—it is all that is promised to us. To make sure that we will belong to the next moment, and the one after, we must make promises to each other.

Mutual aid news: I have launched a Al Shams Bazaar shop in order to sell some of the items I’ve been making to support my dear friend Fedaa and her family! Get a lovely piece of tatreez or a print, and directly support a family in Gaza. Conditions continue to be dire and the family only has enough funds left to last about a week. Your support means the world.

Don’t need stuff but want to help? Donations can be made here: Chuffed - Necessities for Fedaa’s Family